Birmingham-born author explores city’s civil rights legacy in new book

Birmingham’s national image is still shaped almost exclusively by a collective memory of the violence that occurred here in the early 1960s at the peak of the Civil Rights Movement.

That violence is captured in the oft-seen newsreels and black and white photos of such events as the deadly bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church and the use of dogs and fire hoses by Birmingham police to attack peaceful Black demonstrators.

Julie Buckner Armstrong, a Birmingham native, had only a superficial knowledge of this history while growing up here in the years following these major events.

However, Armstrong – now an English professor at The University of South Florida in St. Petersburg – learned much more about Birmingham’s historical significance after leaving the city to attend college and pursue her academic career.

She also became a widely respected scholar who studies Southern literature and the literature of civil rights and social justice.

In 2011, Armstrong published “Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching,” a book about the 1918 lynching of a pregnant Black woman in Georgia and the event’s national impact. She has also edited three anthologies of writings about civil rights.

When Armstrong returned to Birmingham after many years away to care for her aging mother, she began pondering the lessons the city might offer to contemporary America, where Blacks and other people of color are still struggling to achieve full acceptance and equality well into the 21st century.

Armstrong began a long effort to study Birmingham’s complex history and to understand the city’s connection to larger stories of oppression and resistance. She also sought to find the significance of this history for herself and her white, working-class family.

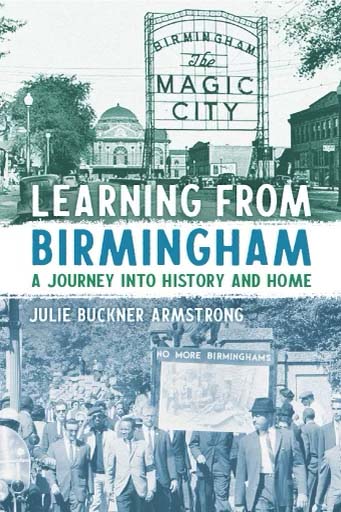

The result – after years of research – is her memoir, “Learning from Birmingham: A Journey into History and Home,” published in May by the University of Alabama Press.

The book offers a skillful portrait of Birmingham and weaves together stories of the author’s family, classmates and others not traditionally associated with Birmingham’s civil rights history, including members of the city’s LGBTQ community.

Armstrong recently responded to some questions about the book from BHMSTR.

When did you first get the notion to write your book about Birmingham?

I have been a civil rights movement educator for more than 20 years, and I’ve written or edited other academic books related to that topic. This book started out very different. I intended to write a book of essays based in obituaries. I wanted to focus on the way that people are talked about there vs. the more complicated ways they lived their lives. But the more I got into that project, the more I realized that most of my subjects were centered on my hometown of Birmingham and most had some connection, direct or tangential, to the civil rights movement, broadly defined. So I refocused my efforts around that topic, to explore the connective threads between past and present, ordinary people and extraordinary events. And the more I explored that, the more I realized that I needed to explore my own connections to local history, especially movement history. It was a way of taking responsibility for a past that still lives with us in the present, in ways we don’t always recognize and acknowledge.

How long did you work on it? Roughly how many interviews did you do?

I worked on the book for about 10 years, the first five sporadically, and the next five in a more focused way. I did a lot of primary research, some of it interviews, some of it reading oral histories and primary documents from various archives, and the rest reading about the history and literature of Birmingham or the movement more generally.

Did writing the book teach you things about Birmingham that you didn’t already know?

Yes and no. A good deal of the book is memoir, mixed in with stories from family, friends and people I have some kind of personal connection with. The funny thing about writing a memoir is that one relies, by necessity, on faulty memory. I had to negotiate between different versions of events: what I remembered versus what others remembered versus what might have been written up in, say, a newspaper account. So, yes, I learned a lot about myself and local history that I thought I already knew but clearly did not. Another part of the equation is that I envisioned my audience as being composed of people who might have an interest in the city but little familiarity with it. I wanted to convey the discrepancy between the iconic, mythical Birmingham frozen in 1963 and – going back the original impetus for the book, those obituaries – the complicated city where I was raised, and that has changed, to some extent, over time. When I give public talks across the country, audiences are often shocked to find that Birmingham is not a “heart of darkness.” It’s pretty, it’s diverse, and it has a large population of political progressives.

Is it healthy for white Southerners to come to terms with their own history and deal with it honestly?

It’s vital for EVERYONE to deal with their history honestly and responsibly. We live in a time that people seem to be afraid of history, especially the kind that is difficult rather than celebratory. Too many people have the (understandable) desire to bracket off history from who they are in the present – that is, all that happened long ago and far away, so it’s “not me.” But the past IS who we are in the present. We’re never going to resolve any of our ongoing social problems until we examine the roots of those problems. Maybe a different way of thinking about it is that a lot of white people especially are ashamed of their Birmingham, or Southern, past — and rightfully so in some cases. But writing a book about Birmingham helped me see it as a place one could also be proud of. Alongside the bad parts are truly great stories of people who were courageous and forward thinking, and changed the world they lived in, in small or large ways. It’s a beautiful, rich history that should be embraced in all its complexity.

Armstrong’s responses have been edited slightly for format and clarity.

For more information about “Learning from Birmingham,” go to uapress.ua.edu.

Armstrong is scheduled to make an appearance at O’Neal Library in Crestline Village on Sat., Nov. 4, at 2 p.m. For details, go to emmetoneal.libnet.info.